In the metal fabrication business, everyone would rather be busy than slow, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

In 2018 Amerequip Corp., a fabricator of custom equipment for the lawn, landscape, agricultural, and construction markets, was trying to keep up with a manufacturing economy that was red-hot. It had just completed a major expansion of its welding and fabricating areas at its main manufacturing facility in Kiel, Wis., in 2017 and boosted its laser cutting capacity with a major investment in cutting machines and a huge 15-tower, 200-shelf automated raw material storage and retrieval system, but it was still having trouble handling all of the new opportunities from its customers.

How fast was the company growing? It had $55 million in sales revenue in 2016 and expects to reach $110 million in 2020.

The challenge was a culture of always trying to fulfill customers’ wishes.

“We simply didn’t want to tell the customer ‘no,’” said Rob Abfall, Amerequip’s chief operating officer.

Amerequip had made significant investments—$25 million alone in capital equipment from 2012 to 2017—to stay on top of all these new opportunities. However, human resources was posing a problem. The fabricator couldn’t find enough workers, and retention was becoming more of an issue as some employees took advantage of the robust manufacturing economy in Wisconsin, finding other employment that may have offered more money or was closer to their homes.

In 2012, 125 people worked for Amerequip; by mid-2017 that number had grown to 300. And more would be needed.

If Amerequip wanted to keep growing, it had to make some changes.

Master Manufacturer

Amerequip’s history dates back almost 100 years. The company began life as the Farm Specialty Manufacturing Co., founded in 1920 by Bruno F. Arps of New Holstein, Wis. Early on it built its reputation as a custom equipment manufacturer, especially unique backhoes, a product the fabricator is still heavily involved in.

One of the more unique products ever made by the company was the Super Snow Bird, an over-the-wheel track system and accompanying front skis that were assembled on a Model A car. The automobile designed for snow was discontinued in 1939, but not before Admiral Richard E. Byrd took a couple with him on his early Antarctic expeditions.

The company was renamed Arps Corp. in 1952 and ultimately Amerequip in 1983, following an ownership change. By then it had its original manufacturing facility in New Holstein and a newer facility in nearby Kiel.

Until 1983 the manufacturer had mainly focused on its own line of products, which included medium-duty backhoes for compact utility tractors, front-end loaders, front and rear blades, and post hole diggers, which had been marketed through distributors and dealers. After new ownership came in, the fabricator turned its focus to building products for OEMs and taking on more contract manufacturing work.

That business model still exists today as it builds familiar items, such as backhoes, and newer products such as mower decks and snow blowers for skid steers. It even builds complete end products, such as commercial mowers. Abfall said that the company’s design engineering, fabricating, assembling, painting, and testing capabilities have proven to be a winning combination, enticing its long-term customers to throw more work their way.

“All of this growth has been organic. We did not go out and acquire any other businesses,” Abfall said.

In 2018 Abfall said he knew something had to change. (Amerequip President and CEO Mike VanderZanden told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in October 2018 that the company had turned away about $10 million in business because it couldn’t hire enough people.) Amerequip struggled to keep up with work, and if it were to continue its successful pattern of year-over-year growth, it needed to reduce employee turnover and straighten out some of its processes.

Figuring out the People End of It

One of the first steps Amerequip took was to renegotiate the contract with the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, which represented its employees. The company raised its starting wage to more than $15 per hour. Starting wages for welders topped $18. It also gave significant raises beyond what the original contract stipulated.

Then the fabricator made a major shift in its work hours. It added a weekend shift at the Kiel facility, something that Abfall said he had never done before. The idea came from the welding department, he said.

Now Amerequip has morning and afternoon shifts that run 10 hours each, Monday through Thursday, and a weekend shift that comprises three 12-hour days, Friday to Sunday. Employees that work the weekend shift get paid for 40 hours.

“People want time, and it’s even more so now than it was 15 years ago. In my experience, people used to want more overtime. They didn’t want as much free time,” Abfall said. “But it’s really changed. It’s evolved.”

To fill up the talent pipeline, the fabricator is looking to strengthen its partnerships with local high schools and technical schools. The company offers apprenticeships, so that students can attend classes at the technical school while simultaneously learning on the job—and getting paid for it.

Abfall said that the company has committed to doing a better job in internal posting of jobs and communicating about opportunities. Working through the local technical schools’ welding boot camps, a person can become trained to take on basic welding tasks, which comes with the opportunity to make $3 an hour more than other roles in the facility.

Amerequip now employs 385 people, with 285 of those being hourly workers. It has about 70 welders.

Abfall said that, in combination with finding nearby partner companies that can assist with fabricating, welding, and finishing tasks when job orders exceed capacity, stabilizing the employee turnover has proven beneficial in allowing the company to focus on internal improvements, which ultimately leads to more efficiency on the shop floor.

“We want to do more for less,” he said. “We want to grow our customers.”

Big-time Laser Cutting

In addition to the 71,000-square-foot welding shop expansion in 2014, Amerequip added an 83,000-sq.-ft. addition in 2016 to house its laser cutting and bending operations. Until then some of the fabricating and welding work took place at its 40,000-sq.-ft. New Holstein plant, which is now being used exclusively for cylinder manufacturing. Needless to say, the added space gave the fabricator room to maximize its material flow and plan for the future.

With its capital equipment investments over the last couple of years, the company won’t have to worry about laser cutting or bending being its bottleneck. As of 2018, Amerequip had six Mitsubishi CO2 laser cutting machines attached to a River automated material storage and retrieval system that keeps the equipment constantly supplied with sheets to be cut. (A monorail runs the entire length of the system to insert and retrieve “cartridges” of raw material.) The system can supply material to nine lasers and be expanded to 18 towers and 250 shelves to accommodate 12 laser cutting machines. MC Machinery Systems supplied the laser cutting machines and the material handling system.

Bob Heus, the company’s operations manager, said the big benefit of this automated material handling system is that no lift trucks are needed for material movement. An overhead crane moves the raw stock from trucks at the nearby dock in the rear of the building to the loading point for material storage. The monorail takes the cartridge and inserts it into one of the open shelves.

Heus added that the CO2 laser technology really makes sense for the material mix that Amerequip cuts on a regular basis. Sheet thickness can run anywhere from 20 gauge to 1 inch, but a majority of the steel being processed through the laser system is 0.375 to 0.25 in.

The fabricator also has a pretreatment system, installed in 2017, in which all parts are processed. The acid bath removes the oxidized edges and slag from the laser-cut parts. The bath allows Amerequip to cut with oxygen as the laser cutting assist gas instead of the more expensive nitrogen, which many other fabricators use to avoid the oxidized edges that come with oxygen-assisted laser cutting. (Oxidized edges act as a barrier to superior paint and powder coating adhesion on metal parts.)

“Of course, if we didn’t have the pickling system and had to go back to all manual removal of oxide, the nitrogen cutting starts to become more attractive,” Heus said.

Although fiber laser technology is not part of the mix right now, Abfall said that they are keeping an eye on it if the need is there for further expansion of the laser cutting system. In the near term, Heus said the focus is on looking at automation that might be able to assist with parts sorting after skeletons are unloaded from the laser cutting bed.

Around the same time the laser cutting system was being installed, the fabricator also upgraded its bending capabilities with two SafanDarley servo-electric E Brakes, one that is 40 tons and the other which is 120 tons. They joined the company’s two hydraulic press brakes.

Abfall said the brakes have been instrumental in helping the bending department keep up with the efficient delivery of laser-cut parts. The tooling setups can be done quickly because of the Wila tooling design, and software that simulates the bend process in 3D helps the operator to see what is about to happen instead of having to visualize it on his own.

The press brakes are able to hold angle tolerances of 0.5 degree. That accuracy, along with the precise cuts delivered by the laser, has allowed many parts to bypass the machine shop, which was not the case about three years ago. Heus credited the new equipment for this newfound accuracy, but also said that working more closely with engineering has revealed that some parts may not require as tight of a tolerance as was originally specified. The end result is that the welding department is getting a lot better set of parts to join.

Work to Do in Welding

Like many other metal fabricating operations, Amerequip would like to get more productivity out of its welding department. With the labor situation somewhat settled, attention is now being turned to optimizing the robotic welding effort.

The fabricator has 10 Lincoln Electric welding cells with FANUC robots. All the cells have dual fixturing tables, either left- and right-hand or front and back, which enable welding to be done on one side as the fixtures are unloaded and loaded on the other side.

Right now the welding department is at about 50 to 60 percent utilization, according to Abfall. Heus is charged with finding ways to improve that.

One of the first things he did was eliminate the requirement that every weldment has to be tack welded before being placed in the fixture. The company had followed this approach for almost the last four years. Now a part can be put in the fixture, and it’s ready for the robot.

Heus said the consistent and high-quality parts coming from the fabrication department help with this place-and-go approach to robotic welding. His next project is looking for existing parts that are good candidates to be moved to the robotic welding cell.

Another aspect of this process is to investigate more cost-efficient ways to fabricate parts for customers—even if the part is not being welded by Amerequip. A recent award-winning cast part is a good example of this type of cost-saving conversation.

When Amerequip was looking at rising volumes for an 11-piece steel swing frame that was used on a compact utility tractor backhoe attachment, it realized that it might be more cost-effective to have it cast instead of fabricated. Additionally, working with one weldment that is delivered to final assembly instead of having to laser-cut and weld the 11 pieces to create the same thing is always going to be helpful in streamlining assembly and meeting on-time delivery goals.

Amerequip worked with Neenah Foundry, Neenah, Wis., starting in April 2018. After almost a year of back and forth and finally testing, a new casting will make its debut in a 2020 backhoe product. The casting weighs 5.6 lbs. less than the original fabricated and welded predecessor. Holes and mating features are now machined into the casting, instead of laser cutting them early on, which allows for tighter tolerances and more accurate assembly. The project won the 2019 Casting of the Year award from the American Foundry Society and Metal Casting Design & Purchasing magazine.

“With everything that has changed over the last six months, now everybody really is being able to focus more on cost,” Abfall said.

Boosting Finishing Efficiency

The finishing department, where parts move from welding, is another area where the operations team will be working to streamline product flow. Amerequip has the pretreatment bath; an e-coat tank; two paint-application booths with automated, reciprocating guns; and manual touchup areas for complex parts that didn’t receive complete paint coverage in the automated booths. (E-coat, short for electrophoretic coating, is known for its corrosion-resistance abilities. In this process a metal part is dipped into a tank containing a water-based solution mixed with a paint emulsion. An electric voltage is applied to the part, causing the paint emulsion to adhere to the part.)

Another area of focus is perhaps creating one part load-off area instead of separate ones that dot the large assembly area. The idea is that flow would be simplified on the shop floor if painted parts were exiting from one area and directly into value streams.

Abfall said another project is investigating ways to add capacity. A relationship with another custom finisher in Wisconsin has helped to take some pressure off the finishing department and ease the bottleneck, but company leadership is considering expansion of the paint department or acquiring capacity to provide a more permanent solution.

The Pull of Assembly

When a company is making end products, fabricating large assemblies, and preparing kits for major OEM customers, it has to have its assembly process down. Heus said Amerequip has been fortunate in creating an environment where manufacturing activity is now linked closely to real demand, not unrealistic production schedules or the personal desires of machine operators.

“Within the last year, we have become more proactive versus reactive. These changes enable us to make sure we can meet the demand versus running into a wall and falling behind,” Heus said.

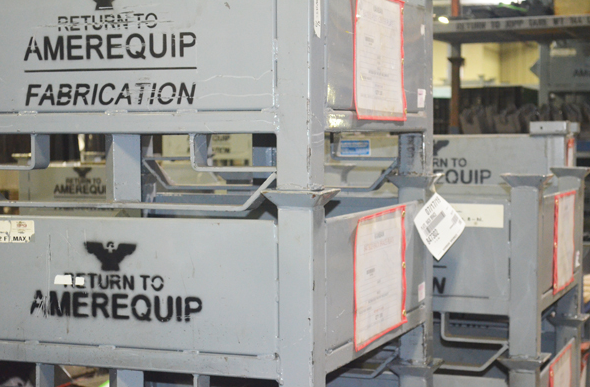

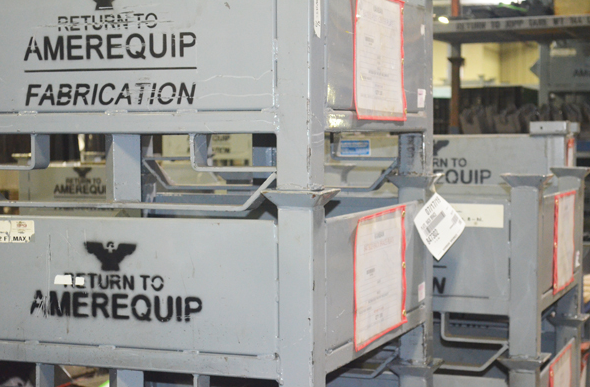

This “pull” demand, instead of “push” demand in which the fabricating and welding department just produce parts and send them to the finishing and assembly departments even if they may not really be ready for them, is symbolized by pallets and totes found throughout the assembly area. When one is emptied, the accompanying router card and pallet/tote goes all the way back to the front of the system, the fabrication department, and a production order is triggered. It then flows through welding and finishing before arriving back in assembly.

Based on product volume, the number of pallets and totes that feed assembly varies. For instance, if an assembly cell requires 100 parts per day, six totes with 25 parts in each might be staged nearby, providing the cell with a day and a half of product. The key is to keep production going to meet demand, but not building too much.

“It’s a truer sense of what needs to be done instead of having the MRP system pushing the schedule,” Abfall said.

Amerequip is taking the same approach with its vendors, encouraging them to more actively manage their delivery of products. Again, the goal is to have the right amount of purchased parts at the right time.

The exercise is bearing some fruit after only a few months. Abfall said the company has been able to take out about $5 million worth of inventory. Work continues to introduce more just-in-time programs with vendors, so more improvement in this area is likely.

Ready for Growth

The quest to find quality workers is ongoing, but a lot of the churn has settled for the time being. After almost doubling the manufacturing square footage over the last four years, the company has achieved a comfortable production rhythm. Everyone at Amerequip has had a chance to catch their breath and even sit down for an interview with The FABRICATOR.

But the metal fabricating industry is not dominated by companies that take it easy. It’s a constant push to serve customers better, and if a fabricator does it well, often more opportunities arise.

That’s where Amerequip now finds itself. It needs to find more painting capacity. It’s also giving thought to how might be the best way to stage product for shipping to customers. Meanwhile, everyone is working to find the best and most cost-effective ways to build parts and end products for customers.

There’s no guarantee that these and other improvements will get Amerequip to its goal of $150 million in sales by 2023, but all of these recent changes create a solid foundation from which to make a solid go of it.

FROM thefabricator

BY DAN DAVIS